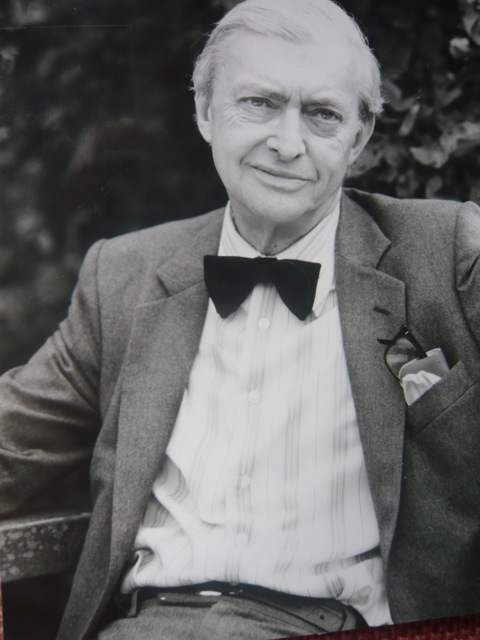

W.H. Auden (1907—1973) is an English poet, who significantly influenced the direction of 20th century poetry. Although raised in the church, he grew into atheism, even as he found poetry to be his vocation. By the late 1930s, however, he faced troubling questions that eventually led him to return to church, and to declare himself a Christian. One such question was, if he’d been given the gift of poetry, who was the giver?

He moved to the United States in 1939 and began teaching at the University of Michigan. In 1948 Auden won the Pulitzer Prize for his book The Age of Anxiety. From 1956 to 1961, he was Professor of Poetry at Oxford.

Auden had for years been a practicing homosexual — even though, even in his pre-conversion days, he saw this as morally wrong. It remained an issue for him for the rest of his life, even as he and his long-time partner, continued to live together in a passionless relationship.

In his latter years, he divided his time between New York City and Austria. He died in Vienna on September 29, 1973. The following poem appeared in 1942.

For The Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio

Well, so that is that. Now we must dismantle the tree,

Putting the decorations back into their cardboard boxes —

Some have got broken — and carrying them up to the attic.

The holly and the mistletoe must be taken down and burnt,

And the children got ready for school. There are enough

Left-overs to do, warmed-up, for the rest of the week —

Not that we have much appetite, having drunk such a lot,

Stayed up so late, attempted — quite unsuccessfully —

To love all of our relatives, and in general

Grossly overestimated our powers. Once again

As in previous years we have seen the actual Vision and failed

To do more than entertain it as an agreeable

Possibility, once again we have sent Him away,

Begging though to remain His disobedient servant,

The promising child who cannot keep His word for long.

The Christmas Feast is already a fading memory,

And already the mind begins to be vaguely aware

Of an unpleasant whiff of apprehension at the thought

Of Lent and Good Friday which cannot, after all, now

Be very far off. But, for the time being, here we all are,

Back in the moderate Aristotelian city

Of darning and the Eight-Fifteen, where Euclid's geometry

And Newton's mechanics would account for our experience,

And the kitchen table exists because I scrub it.

It seems to have shrunk during the holidays. The streets

Are much narrower than we remembered; we had forgotten

The office was as depressing as this. To those who have seen

The Child, however dimly, however incredulously,

The Time Being is, in a sense, the most trying time of all.

For the innocent children who whispered so excitedly

Outside the locked door where they knew the presents to be

Grew up when it opened. Now, recollecting that moment

We can repress the joy, but the guilt remains conscious;

Remembering the stable where for once in our lives

Everything became a You and nothing was an It.

And craving the sensation but ignoring the cause,

We look round for something, no matter what, to inhibit

Our self-reflection, and the obvious thing for that purpose

Would be some great suffering. So, once we have met the Son,

We are tempted ever after to pray to the Father;

"Lead us into temptation and evil for our sake."

They will come, all right, don't worry; probably in a form

That we do not expect, and certainly with a force

More dreadful than we can imagine. In the meantime

There are bills to be paid, machines to keep in repair,

Irregular verbs to learn, the Time Being to redeem

From insignificance. The happy morning is over,

The night of agony still to come; the time is noon:

When the Spirit must practice his scales of rejoicing

Without even a hostile audience, and the Soul endure

A silence that is neither for nor against her faith

That God's Will will be done, That, in spite of her prayers,

God will cheat no one, not even the world of its triumph.

*This is the third Kingdom Poets post about W.H. Auden:

first post, second post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections

including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the

point-of-view of angels. His books are available through

Wipf & Stock.

Monday, December 30, 2024

Monday, December 23, 2024

E.E. Cummings*

E.E. Cummings (1894—1962) is considered one of the most important poets of the 20th century. Like my own grandfather, he served in the ambulance corps during WWI. His first collection Tulips and Chimneys appeared in 1923. James Dickey once wrote, "I think that Cummings is a daringly original poet, with more vitality and more sheer, uncompromising talent than any other living American writer."

Although Cummings is known particularly for his innovation, and is associated with modernism, his divergences are primarily built upon traditional poetic structures. His variations often consist of using words in unexpected ways — making it seem like he’s used the wrong word or placed it in the wrong part of the sentence. By doing so he elicits sudden stops and reassessments of language and meaning for the reader.

Rushworth M. Kidder wrote in The Christian Science Monitor:

----“His poetry, in many ways, is the chart of his search for a

----redeemer — for something that would save a world made ugly

----by the two world wars through which he lived, and made sordid

----by the materialism that spawned them. In his early years he

----sought salvation in love poetry. As he progressed he came to

----seek it more and more in a sense of deity, in a supreme source

----of goodness that appears in his poetry as everything from a

----vague notion of nature's beneficence to a vision of something

----very like the Christian's God.”

The following poem — which first appeared in The Atlantic in December 1956 — is clearly a sonnet, although it uses minimal rhyme.

Christmas Poem

from spiraling ecstatically this

proud nowhere of earth’s most prodigious night

blossoms a newborn babe: around him, eyes

— gifted with every keener appetite

than mere unmiracle can quite appease—

humbly in their imagined bodies kneel

(over time space doom dream while floats the whole

perhapsless mystery of paradise)

mind without soul may blast some universe

to might have been, and stop ten thousand stars

but not one heartbeat of this child; nor shall

even prevail a million questionings

against the silence of his mother’s smile—

— whose only secret all creation sings

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about E.E. Cummings: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Although Cummings is known particularly for his innovation, and is associated with modernism, his divergences are primarily built upon traditional poetic structures. His variations often consist of using words in unexpected ways — making it seem like he’s used the wrong word or placed it in the wrong part of the sentence. By doing so he elicits sudden stops and reassessments of language and meaning for the reader.

Rushworth M. Kidder wrote in The Christian Science Monitor:

----“His poetry, in many ways, is the chart of his search for a

----redeemer — for something that would save a world made ugly

----by the two world wars through which he lived, and made sordid

----by the materialism that spawned them. In his early years he

----sought salvation in love poetry. As he progressed he came to

----seek it more and more in a sense of deity, in a supreme source

----of goodness that appears in his poetry as everything from a

----vague notion of nature's beneficence to a vision of something

----very like the Christian's God.”

The following poem — which first appeared in The Atlantic in December 1956 — is clearly a sonnet, although it uses minimal rhyme.

Christmas Poem

from spiraling ecstatically this

proud nowhere of earth’s most prodigious night

blossoms a newborn babe: around him, eyes

— gifted with every keener appetite

than mere unmiracle can quite appease—

humbly in their imagined bodies kneel

(over time space doom dream while floats the whole

perhapsless mystery of paradise)

mind without soul may blast some universe

to might have been, and stop ten thousand stars

but not one heartbeat of this child; nor shall

even prevail a million questionings

against the silence of his mother’s smile—

— whose only secret all creation sings

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about E.E. Cummings: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, December 16, 2024

Paul Laurence Dunbar*

Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872—1906) is a poet, novelist, and short story writer from Dayton, Ohio. His parents had both been enslaved in Kentucky before the Civil War. When he was just 16, a Dayton newspaper began to publish his poems.

His mother had learned to read in order to help young Paul with his schooling. Her desire was that he might, some day, become a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church — the first independent black denomination in the United States.

He was the only African-American student at his high school, yet became the president of the school’s literary society. One of his closest friends was Orville Wright — who, along with his brother, were early encouragers of Dunbar’s poetry. They presented it to their father who was a bishop in the Church of the Brethren — the denomination that published his first volume, Oak and Ivy (1893).

Paul Laurence Dunbar eventually published twelve poetry collections, eight books of fiction, and he also wrote the lyrics for the first all-African-American musical performed on Broadway — In Dahomey (1903) — which later toured in both the U.S. and the U.K.

Christmas Carol

----Ring out, ye bells!

----All Nature swells

With gladness at the wondrous story,—

----The world was lorn,

----But Christ is born

To change our sadness into glory.

----Sing, earthlings, sing!

----To-night a King

Hath come from heaven's high throne to bless us.

----The outstretched hand

----O'er all the land

Is raised in pity to caress us.

----Come at his call;

----Be joyful all;

Away with mourning and with sadness!

----The heavenly choir

----With holy fire

Their voices raise in songs of gladness.

----The darkness breaks

----And Dawn awakes,

Her cheeks suffused with youthful blushes.

----The rocks and stones

----In holy tones

Are singing sweeter than the thrushes.

----Then why should we

----In silence be,

When Nature lends her voice to praises;

----When heaven and earth

----Proclaim the truth

Of Him for whom that lone star blazes?

----No, be not still,

----But with a will

Strike all your harps and set them ringing;

----On hill and heath

----Let every breath

Throw all its power into singing!

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Paul Laurence Dunbar: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

His mother had learned to read in order to help young Paul with his schooling. Her desire was that he might, some day, become a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church — the first independent black denomination in the United States.

He was the only African-American student at his high school, yet became the president of the school’s literary society. One of his closest friends was Orville Wright — who, along with his brother, were early encouragers of Dunbar’s poetry. They presented it to their father who was a bishop in the Church of the Brethren — the denomination that published his first volume, Oak and Ivy (1893).

Paul Laurence Dunbar eventually published twelve poetry collections, eight books of fiction, and he also wrote the lyrics for the first all-African-American musical performed on Broadway — In Dahomey (1903) — which later toured in both the U.S. and the U.K.

Christmas Carol

----Ring out, ye bells!

----All Nature swells

With gladness at the wondrous story,—

----The world was lorn,

----But Christ is born

To change our sadness into glory.

----Sing, earthlings, sing!

----To-night a King

Hath come from heaven's high throne to bless us.

----The outstretched hand

----O'er all the land

Is raised in pity to caress us.

----Come at his call;

----Be joyful all;

Away with mourning and with sadness!

----The heavenly choir

----With holy fire

Their voices raise in songs of gladness.

----The darkness breaks

----And Dawn awakes,

Her cheeks suffused with youthful blushes.

----The rocks and stones

----In holy tones

Are singing sweeter than the thrushes.

----Then why should we

----In silence be,

When Nature lends her voice to praises;

----When heaven and earth

----Proclaim the truth

Of Him for whom that lone star blazes?

----No, be not still,

----But with a will

Strike all your harps and set them ringing;

----On hill and heath

----Let every breath

Throw all its power into singing!

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Paul Laurence Dunbar: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, December 9, 2024

Charles Causley*

Charles Causley (1917—2003) is a poet of our times, and yet one more in tune, musically, with the past — becoming at first known for his ballads. He was never a poet of the avant garde — and was called by Dana Gioia, in the late 1990’s, “The most unfashionable poet alive.” He lived a quiet life as a teacher at the same school he had attended, never married, and spent many years caring for his aging mother.

He wrote extensively of his native Cornwall, but also of his world travels. He served in the Royal Navy, and, after completing thirty years as a school teacher, accepted invitations to be writer-in-residence at the University of Western Australia, the Footscray Institute of Technology, Victoria, and the School of Fine Arts, Banff, Alberta.

His first poetry collection, Farewell, Aggie Weston, appeared in 1951; he began to also publish books for children beginning with Figure of 8 in 1969.

In 1984, Gioia said, “Causley’s characteristic mode is often the short narrative…” comparing him to William Blake, his “late eighteenth-century master… [who] provided him a potent example of how the poetic outsider can become a seer.” He added, “The visionary mode has its greatest range of expression in Causley’s religious poetry.”

The following poem is from Charles Causley’s small illustrated book of twelve Christmas poems Bring in the Holly (Frances Lincoln, 1992).

Mary’s Song

Your royal bed

Is made of hay

In a cattle-shed.

Sleep, King Jesus,

Do not fear,

Joseph is watching

And waiting near.

Warm in the wintry air

You lie,

The ox and the donkey

Standing by,

With summer eyes

They seem to say:

Welcome, Jesus,

On Christmas Day!

Sleep, King Jesus:

Your diamond crown

High in the sky

Where the stars look down.

Let your reign

Of love begin,

That all the world

May enter in.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Charles Causley: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

He wrote extensively of his native Cornwall, but also of his world travels. He served in the Royal Navy, and, after completing thirty years as a school teacher, accepted invitations to be writer-in-residence at the University of Western Australia, the Footscray Institute of Technology, Victoria, and the School of Fine Arts, Banff, Alberta.

His first poetry collection, Farewell, Aggie Weston, appeared in 1951; he began to also publish books for children beginning with Figure of 8 in 1969.

In 1984, Gioia said, “Causley’s characteristic mode is often the short narrative…” comparing him to William Blake, his “late eighteenth-century master… [who] provided him a potent example of how the poetic outsider can become a seer.” He added, “The visionary mode has its greatest range of expression in Causley’s religious poetry.”

The following poem is from Charles Causley’s small illustrated book of twelve Christmas poems Bring in the Holly (Frances Lincoln, 1992).

Mary’s Song

Your royal bed

Is made of hay

In a cattle-shed.

Sleep, King Jesus,

Do not fear,

Joseph is watching

And waiting near.

Warm in the wintry air

You lie,

The ox and the donkey

Standing by,

With summer eyes

They seem to say:

Welcome, Jesus,

On Christmas Day!

Sleep, King Jesus:

Your diamond crown

High in the sky

Where the stars look down.

Let your reign

Of love begin,

That all the world

May enter in.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Charles Causley: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, December 2, 2024

Mary of Nazareth

Mary is the earthly mother of Jesus, who by the power of the Holy Spirit, though she was still a virgin, conceived God’s own son. The story in Luke’s account begins with Zacharias — a man in the priestly line — being told by the angel Gabriel that he and his wife, Elizabeth, will have a child in their old age. This child was to be the one to go before the coming of the Christ to prepare the people for the coming of the Lord.

When Gabriel announces to Mary that she is to become the mother of the Messiah, he also reveals that her cousin Elizabeth is miraculously six-months-pregnant.

The following canticle is an exclamation of praise (here in the New King James Version) which was spoken by Mary to her cousin Elizabeth, whom she was visiting in the Judean hill country. It is known as “The Magnificat,” which is Latin for “magnifies” as spoken in the opening line.

The Magnificat

My soul magnifies the Lord,

And my spirit has rejoiced in God my Saviour.

For He has regarded the lowly state of His maidservant;

For behold, henceforth all generations will call me blessed.

For He who is mighty has done great things for me,

And holy is His name.

And His mercy is on those who fear Him

From generation to generation.

He has shown strength with His arm;

He has scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.

He has put down the mighty from their thrones,

And exalted the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things,

And the rich He has sent away empty.

He has helped His servant Israel,

In remembrance of His mercy,

As He spoke to our fathers,

To Abraham and to his seed forever.

(For those who ponder, like I have —

----How did this navigate its way

----into Luke’s account?

— check out my poem “Magnificat” from my poetry collection Poiema.)

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

When Gabriel announces to Mary that she is to become the mother of the Messiah, he also reveals that her cousin Elizabeth is miraculously six-months-pregnant.

The following canticle is an exclamation of praise (here in the New King James Version) which was spoken by Mary to her cousin Elizabeth, whom she was visiting in the Judean hill country. It is known as “The Magnificat,” which is Latin for “magnifies” as spoken in the opening line.

The Magnificat

My soul magnifies the Lord,

And my spirit has rejoiced in God my Saviour.

For He has regarded the lowly state of His maidservant;

For behold, henceforth all generations will call me blessed.

For He who is mighty has done great things for me,

And holy is His name.

And His mercy is on those who fear Him

From generation to generation.

He has shown strength with His arm;

He has scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.

He has put down the mighty from their thrones,

And exalted the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things,

And the rich He has sent away empty.

He has helped His servant Israel,

In remembrance of His mercy,

As He spoke to our fathers,

To Abraham and to his seed forever.

(For those who ponder, like I have —

----How did this navigate its way

----into Luke’s account?

— check out my poem “Magnificat” from my poetry collection Poiema.)

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, November 25, 2024

Hester Pulter

Hester Pulter (1605–1678) is a writer of poetry and prose who was completely unknown, prior to the discovery of her manuscript at Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, in 1996. Although English, she was born in County Dublin, the eighth of James Ley’s ten children. He was chief justice of the King’s Bench in Ireland, at the time of her birth, but the family returned to England in 1608.

The manuscript of her collected writing demonstrates that she was well educated — not only through the variety of literary genres she mastered, but also through her allusions to classical authors, and her interest in recent scientific discoveries. It contains one hundred and twenty poems and an unfinished prose romance. There is no evidence that her writing was ever published (prior to the 21st century) nor that it was even circulated.

It is interesting to note that John Milton wrote a sonnet in honour of James Ley, addressed to Hester’s sister Lady Margaret Ley which begins: “Daughter to that good Earl…” It was in 1626 that James Ley became the first earl of Marlborough.

She married Arthur Pulter in 1620, several months before she turned 15. They primarily lived at his inherited estate of Broadfield near the village of Cottered in Hertfordshire (pictured above). Although Lady Hester Pulter gave birth to eight daughters and seven sons — mentioned by name in her poems — she only predeceased two of them.

The Desire

Dear God, vouchsafe from Thy high throne

To see my tears, and hear my moan;

For I, in heaven and earth, have none

To pity me

In my dejected sad estate,

Wherein I’m thrown by adverse fate,

And hope in none till my last date

But only Thee.

O then be pleased my dust to raise,

To sing thy everlasting praise

In those celestial unknown lays,

With life and love.

Then shall I leave these terrene toys,

Obliviating past annoys,

And be involved in endless joys

With Thee above.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

The manuscript of her collected writing demonstrates that she was well educated — not only through the variety of literary genres she mastered, but also through her allusions to classical authors, and her interest in recent scientific discoveries. It contains one hundred and twenty poems and an unfinished prose romance. There is no evidence that her writing was ever published (prior to the 21st century) nor that it was even circulated.

It is interesting to note that John Milton wrote a sonnet in honour of James Ley, addressed to Hester’s sister Lady Margaret Ley which begins: “Daughter to that good Earl…” It was in 1626 that James Ley became the first earl of Marlborough.

She married Arthur Pulter in 1620, several months before she turned 15. They primarily lived at his inherited estate of Broadfield near the village of Cottered in Hertfordshire (pictured above). Although Lady Hester Pulter gave birth to eight daughters and seven sons — mentioned by name in her poems — she only predeceased two of them.

The Desire

Dear God, vouchsafe from Thy high throne

To see my tears, and hear my moan;

For I, in heaven and earth, have none

To pity me

In my dejected sad estate,

Wherein I’m thrown by adverse fate,

And hope in none till my last date

But only Thee.

O then be pleased my dust to raise,

To sing thy everlasting praise

In those celestial unknown lays,

With life and love.

Then shall I leave these terrene toys,

Obliviating past annoys,

And be involved in endless joys

With Thee above.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, November 18, 2024

Maurice Manning*

Maurice Manning is a Kentucky poet, who creates the persona of a backwoods bumpkin in his poetry. His voice is cunning, and precise in its playful images, using a disarming, unhurried conversational tone that combines humour with the simplicity and beauty of life in rural landscapes. Although, he is a professor of English and creative writing at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, and in the Warren Wilson College MFA Program for Writers in North Carolina, he still lives with his family on a small twenty-acre farm. He is vice chancellor of the Fellowship of Southern Writers.

The following poem comes from Snakedoctor (2023, Copper Canyon) which is his eighth poetry collection.

The Red Chair

Believing and being hopeful and praying

are sometimes not enough to do

whatever it is I think I need—

a sort of peace in the valley for me.

But it’s truer to say my course goes through

the darker valley of the shadow.

And the shadow is proverbial,

of course, hard to describe, but the psalm

addresses it well enough. My soul

has been restored a thousand times,

but then it languishes. I get it—

nothing is easy, the struggle is part

of the so-called journey. The journey

must be proverbial too—I mean,

its not like I’m going anywhere,

just sitting in my silent room.

I sit a lot in a red chair.

I stare into space and sometimes

I don’t feel anything at all.

There’s probably something underneath

I’m missing or not fully getting.

But that’s part of it all, to be

in the dark, unknowing. To be unknowing

is a biggie when it comes to faith.

I wouldn’t want to know it all,

to have a vision so complete

you don’t have any doubts or wonders.

Why I must suffer and impair

myself in order to feel the depth

of love is a total mystery

to me. I’d prefer to go outside

and simply be alive in the green

and weather. Oh, I can do that well

enough, and have the whole transcendent

thing, but then the darkness like

a specter comes to rest beside me,

twitching, and everything becomes

abstract, proverbial, and low.

And I think, ironically, it’s dark,

It’s utter dark, this thing I must

Pass through. And thus the red chair

I occupy, from which I see

the world and am involved in love.

I’m so involved with love it’s hard

to fathom, hard to tell how much.

From my perspective, my love for the world

does not have end and has no measure.

There is no poetry in that

or a man sitting in a red chair.

Posted with permission of the poet.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Maurice Manning: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

The following poem comes from Snakedoctor (2023, Copper Canyon) which is his eighth poetry collection.

The Red Chair

Believing and being hopeful and praying

are sometimes not enough to do

whatever it is I think I need—

a sort of peace in the valley for me.

But it’s truer to say my course goes through

the darker valley of the shadow.

And the shadow is proverbial,

of course, hard to describe, but the psalm

addresses it well enough. My soul

has been restored a thousand times,

but then it languishes. I get it—

nothing is easy, the struggle is part

of the so-called journey. The journey

must be proverbial too—I mean,

its not like I’m going anywhere,

just sitting in my silent room.

I sit a lot in a red chair.

I stare into space and sometimes

I don’t feel anything at all.

There’s probably something underneath

I’m missing or not fully getting.

But that’s part of it all, to be

in the dark, unknowing. To be unknowing

is a biggie when it comes to faith.

I wouldn’t want to know it all,

to have a vision so complete

you don’t have any doubts or wonders.

Why I must suffer and impair

myself in order to feel the depth

of love is a total mystery

to me. I’d prefer to go outside

and simply be alive in the green

and weather. Oh, I can do that well

enough, and have the whole transcendent

thing, but then the darkness like

a specter comes to rest beside me,

twitching, and everything becomes

abstract, proverbial, and low.

And I think, ironically, it’s dark,

It’s utter dark, this thing I must

Pass through. And thus the red chair

I occupy, from which I see

the world and am involved in love.

I’m so involved with love it’s hard

to fathom, hard to tell how much.

From my perspective, my love for the world

does not have end and has no measure.

There is no poetry in that

or a man sitting in a red chair.

Posted with permission of the poet.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Maurice Manning: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, November 11, 2024

Vittoria Colonna*

Vittoria Colonna (1492—1547) is an Italian poet, who was also an influential patron of the arts. She is the first woman to have published a poetry collection under her own name. After her husband died at war, she wrote many love poems to his memory which became popular.

During the 1530s she became active in religious reform, and began writing love sonnets addressed to God — which became even more influential. She pushed the traditional Petrarchan form in a new direction to express her relationship with Christ. The first edition of her Rime was published in 1538, and appeared in twelve further editions before her death.

In 1531, Colonna commissioned Titian to paint a large portrait of Mary Magdalene — one of the figures of female spirituality from scripture and early church history she selected as role models for herself and other Christian women.

She became close friends with Michelangelo — influencing his poetry, and sharing the common conviction that faith was to be experienced personally, rather than merely dictated by the church. They both believed that one of the best ways to enhance such faith was through art. She commissioned his black chalk drawing of the Virgin Mary, Pietà for Vittoria Colonna (1540) for her personal meditation.

The following translation is by Jan Zwicky and appears in in Burl Horniachek’s anthology, To Heaven’s Rim: The Kingdom Poets Book of World Christian Poetry.

Sonnets for Michelangelo — 41

When to the one he most loved, Jesus

opened what was in his heart,

when he spoke of the betrayal, the plot

that was to come, it broke

the heart inside his friend. In silence—

for the others must not know—

the tears cut gutters in his face.

But seeing this,

his master held him to his breast,

and before the ditch of pain

had closed inside, had closed his eyes

in sleep.

No eagle ever flew as high

as the divine one in the moment of that falling.

This was God, who was himself alone,

both light and mirror. His rest

true rest, his sleep

true sleep, and peace.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Vittoria Colonna: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

During the 1530s she became active in religious reform, and began writing love sonnets addressed to God — which became even more influential. She pushed the traditional Petrarchan form in a new direction to express her relationship with Christ. The first edition of her Rime was published in 1538, and appeared in twelve further editions before her death.

In 1531, Colonna commissioned Titian to paint a large portrait of Mary Magdalene — one of the figures of female spirituality from scripture and early church history she selected as role models for herself and other Christian women.

She became close friends with Michelangelo — influencing his poetry, and sharing the common conviction that faith was to be experienced personally, rather than merely dictated by the church. They both believed that one of the best ways to enhance such faith was through art. She commissioned his black chalk drawing of the Virgin Mary, Pietà for Vittoria Colonna (1540) for her personal meditation.

The following translation is by Jan Zwicky and appears in in Burl Horniachek’s anthology, To Heaven’s Rim: The Kingdom Poets Book of World Christian Poetry.

Sonnets for Michelangelo — 41

When to the one he most loved, Jesus

opened what was in his heart,

when he spoke of the betrayal, the plot

that was to come, it broke

the heart inside his friend. In silence—

for the others must not know—

the tears cut gutters in his face.

But seeing this,

his master held him to his breast,

and before the ditch of pain

had closed inside, had closed his eyes

in sleep.

No eagle ever flew as high

as the divine one in the moment of that falling.

This was God, who was himself alone,

both light and mirror. His rest

true rest, his sleep

true sleep, and peace.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Vittoria Colonna: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, November 4, 2024

Mia Anderson

Mia Anderson is a Canadian poet, Anglican priest, and retired actress. She is the author of seven poetry collections — including her brand new book O is for Christmas: a Midwinter Night's Dream (2024, St Thomas Poetry Series). Her first collection Appetite appeared from Brick Books in 1988. Around that time she twice won the Malahat Long Poem Prize.

She spent some 25 years as an actress in Canada and Britain — including five seasons at Ontario’s Stratford Festival — but left that behind to receive her MDiv in 2000 to become a priest. With her fourth book The Sunrise Liturgy (2012, Wipf & Stock), her most theological book to date, she joined the long tradition within the Anglican Church of poet-priests.

The foreword to her new book is written by the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams.

In 2013, the following poem won the $20,000 Montreal International Poetry Prize.

The Antenna

For Mike Endicott

The antenna is a growth not always

functional in all people.

Some can hoist their antenna with

remarkable ease—like greased lightning.

In some it is broken, stuck there in its old winged

fin socket way down under the shiny surface

never to issue forth.

Others make do with a little mobility,

a little reception, a sudden spurt of music

and joy, an aberrant hope.

And some—the crazies,

the fools of God—drive around

or sit or even sleep

with this great thin-as-a-thread

home-cobbled monkey-wrenched filament

teetering above their heads

and picking up the great I AM like

some hacker getting Patmos on his toaster.

And some, with WD40 or jig-a-loo

or repeated attempts to pry the thing up

or chisel at the socket

do not give up on this antenna

because they have heard of how it works

sometimes, how when the nights are clear

and the stars just so and the new moon has all but set,

the distant music of the spheres is transformative

and they believe in the transformation.

It is the antenna they have difficulty believing in.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

She spent some 25 years as an actress in Canada and Britain — including five seasons at Ontario’s Stratford Festival — but left that behind to receive her MDiv in 2000 to become a priest. With her fourth book The Sunrise Liturgy (2012, Wipf & Stock), her most theological book to date, she joined the long tradition within the Anglican Church of poet-priests.

The foreword to her new book is written by the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams.

In 2013, the following poem won the $20,000 Montreal International Poetry Prize.

The Antenna

For Mike Endicott

The antenna is a growth not always

functional in all people.

Some can hoist their antenna with

remarkable ease—like greased lightning.

In some it is broken, stuck there in its old winged

fin socket way down under the shiny surface

never to issue forth.

Others make do with a little mobility,

a little reception, a sudden spurt of music

and joy, an aberrant hope.

And some—the crazies,

the fools of God—drive around

or sit or even sleep

with this great thin-as-a-thread

home-cobbled monkey-wrenched filament

teetering above their heads

and picking up the great I AM like

some hacker getting Patmos on his toaster.

And some, with WD40 or jig-a-loo

or repeated attempts to pry the thing up

or chisel at the socket

do not give up on this antenna

because they have heard of how it works

sometimes, how when the nights are clear

and the stars just so and the new moon has all but set,

the distant music of the spheres is transformative

and they believe in the transformation.

It is the antenna they have difficulty believing in.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, October 28, 2024

James Matthew Wilson

James Matthew Wilson is the founding director of the MFA program in Creative Writing at the University of Saint Thomas in Texas, and poet-in-residence of the Benedict XVI Institute which is centred in San Diego — although he and his family live in Michigan. He is influential as a poet, critic, and scholar, particularly in Catholic and conservative circles. He regularly contributes to such magazines as First Things, The New Criterion, National Review, and The American Conservative.

Among his fourteen published books are several poetry collections; his latest is Saint Thomas and the Forbidden Birds (Word on Fire, 2024). As a poet he is clearly a formalist, which is evident in his roles as Poetry Editor for Modern Age magazine, and as Series Editor for Colosseum Books.

The following poem first appeared in the 2024 issue of Presence.

A Dedication to My Wife

----of a book of Anne Bradstreet's poems

If ever two were one, then why not we?

We have begot two in our unity

And find these incarnation of our love

Whatever other mercy from above

Rains down on me—the joys of work, the ease

Of sunshine, peace in thought—may He still please

To let me share these goods with you; or, better,

To let us know them in one heart, our letter

Sign with one name, and find in every hour

Not failing moments but a lating power

That, met with suffering or trial, endures,

Like cellared wine grow fine as it matures.

This post was suggested by my friend Burl Horniachek.

Posted with permission of the poet.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Among his fourteen published books are several poetry collections; his latest is Saint Thomas and the Forbidden Birds (Word on Fire, 2024). As a poet he is clearly a formalist, which is evident in his roles as Poetry Editor for Modern Age magazine, and as Series Editor for Colosseum Books.

The following poem first appeared in the 2024 issue of Presence.

A Dedication to My Wife

----of a book of Anne Bradstreet's poems

If ever two were one, then why not we?

We have begot two in our unity

And find these incarnation of our love

Whatever other mercy from above

Rains down on me—the joys of work, the ease

Of sunshine, peace in thought—may He still please

To let me share these goods with you; or, better,

To let us know them in one heart, our letter

Sign with one name, and find in every hour

Not failing moments but a lating power

That, met with suffering or trial, endures,

Like cellared wine grow fine as it matures.

This post was suggested by my friend Burl Horniachek.

Posted with permission of the poet.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, October 21, 2024

Rainer Maria Rilke

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875—1926) is an Austrian poet born in Prague. Although he is not a Christian, he did receive an intensely Catholic upbringing through his mother. This provided him with Christian imagery and stories, which significantly influenced his concepts of the spiritual life as he created his own mythological landscape.

When Rike refers to God he has his own pantheistic ideas in mind — although for a reader with Christian understanding of who God is, the interpretation might often remain orthodox.

Rainer Maria Rilke is known for his lyrical intensity — particularly in his Duino Elegies which begins, Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic / orders? And even if one of them pressed me / suddenly to his heart: I’d be consumed / in his stronger existence…

In my own poem “Response to Rilke” I have my angelic narrator reply,

----There are few angels---to firsthand hear your cries

--------for some circle the earth

----------------turning away terrors you’ve no knowledge of…

----& though I once was called---to oversee your sojourn

----it was never mine---to turn you left or right

---------------------------or hold you in my embrace…

So many translations of Rilke’s poems appear in journals, anthologies, books, and on the internet, including by such noteworthy poets as Seamus Heaney. Since, like most of you, I don’t speak German, I must content myself with English translations, comparing one with another, and hanging onto the versions that grip me most.

I have been arrested by Rilke’s poem “Autumn” (“Herbst” in German) from The Book of Images many times in various translations. The subtleties from one translation to another deepens my appreciation of the original poem.

Susan McLean translates the opening couplet as

----The leaves are falling, falling from on high,

----As if far gardens withered in the sky.

And Robert Klein Engler has the third line read:

----to teeter with the grace of letting go.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The following beautiful version is a translation by Charles L. Cingolani.

Autumn

The leaves fall, as from afar,

as if withered in heaven's remote gardens;

it is with reluctance that they fall.

And during the nights weighty earth falls

from all the stars into solitude.

All of us fall. This hand falls here.

And look at others: All of them fall.

But there is One, Who holds what falls

with infinite tenderness in His hands.

Even though this is my favourite translation, I appreciate some alternate ways certain lines are carried into English.

Edward Snow renders the final couplet as:

----And yet there is One who holds this falling

----with infinite softness in his hands.

And J.B. Leishman translates it:

----And yet there’s One whose gently-holding hands

----This universal falling can’t fall through.

Despite Rilke’s fragmented acceptance of a Biblical concept of God, his poem does draw us toward a beautiful truth.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

When Rike refers to God he has his own pantheistic ideas in mind — although for a reader with Christian understanding of who God is, the interpretation might often remain orthodox.

Rainer Maria Rilke is known for his lyrical intensity — particularly in his Duino Elegies which begins, Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic / orders? And even if one of them pressed me / suddenly to his heart: I’d be consumed / in his stronger existence…

In my own poem “Response to Rilke” I have my angelic narrator reply,

----There are few angels---to firsthand hear your cries

--------for some circle the earth

----------------turning away terrors you’ve no knowledge of…

----& though I once was called---to oversee your sojourn

----it was never mine---to turn you left or right

---------------------------or hold you in my embrace…

So many translations of Rilke’s poems appear in journals, anthologies, books, and on the internet, including by such noteworthy poets as Seamus Heaney. Since, like most of you, I don’t speak German, I must content myself with English translations, comparing one with another, and hanging onto the versions that grip me most.

I have been arrested by Rilke’s poem “Autumn” (“Herbst” in German) from The Book of Images many times in various translations. The subtleties from one translation to another deepens my appreciation of the original poem.

Susan McLean translates the opening couplet as

----The leaves are falling, falling from on high,

----As if far gardens withered in the sky.

And Robert Klein Engler has the third line read:

----to teeter with the grace of letting go.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The following beautiful version is a translation by Charles L. Cingolani.

Autumn

The leaves fall, as from afar,

as if withered in heaven's remote gardens;

it is with reluctance that they fall.

And during the nights weighty earth falls

from all the stars into solitude.

All of us fall. This hand falls here.

And look at others: All of them fall.

But there is One, Who holds what falls

with infinite tenderness in His hands.

Even though this is my favourite translation, I appreciate some alternate ways certain lines are carried into English.

Edward Snow renders the final couplet as:

----And yet there is One who holds this falling

----with infinite softness in his hands.

And J.B. Leishman translates it:

----And yet there’s One whose gently-holding hands

----This universal falling can’t fall through.

Despite Rilke’s fragmented acceptance of a Biblical concept of God, his poem does draw us toward a beautiful truth.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, October 14, 2024

Stella Nesanovich

Stella Nesanovich is a poet who was born and raised in New Orleans. She has published two collections: Vespers at Mount Angel (2004, Xavier Review Press) and Colors of the River (2015, Yellow Flag). She has also published four chapbooks. She is Professor Emerita of English from McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

Philip C. Kolin said when Colors of the River was about to appear, “With her exquisite new collection, Stella Nesanovich is undoubtedly one of Louisiana’s most gifted poets and a contributor to the Southern elegiac tradition…”

Since that time, her poem “Everyday Grace” has received significant attention after it first appeared in the literary journal Third Wednesday in 2016. Ted Kooser featured it in “American Life in Poetry” — a column which was included in numerous newspapers. “Everyday Grace” can be read on the website of The Poetry Foundation and has been posted to many other internet sites.

The following poem first appeared at Reformed Journal.

Blue Light

The color of deep ice, the blue

frozen in crevasses, a hue

like none other. Such ice

holds memory in that intensity,

a siren song that calls the body.

The early dark of autumn

afternoons, the sky’s cobalt

evoke delight even as sun

departs, leading us

to the depths of night.

One fall, I sat in blue light

cast by stained glass,

a luminous veil. Amazed

by a message I heard

in prayer, I lingered

in tinted brilliance, gazed

about to see if others knew.

Was Gabriel an azure shimmer

when Mary heard him speak

the miracle to grace her life?

Often our answered prayers

are wisps of such light.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Philip C. Kolin said when Colors of the River was about to appear, “With her exquisite new collection, Stella Nesanovich is undoubtedly one of Louisiana’s most gifted poets and a contributor to the Southern elegiac tradition…”

Since that time, her poem “Everyday Grace” has received significant attention after it first appeared in the literary journal Third Wednesday in 2016. Ted Kooser featured it in “American Life in Poetry” — a column which was included in numerous newspapers. “Everyday Grace” can be read on the website of The Poetry Foundation and has been posted to many other internet sites.

The following poem first appeared at Reformed Journal.

Blue Light

The color of deep ice, the blue

frozen in crevasses, a hue

like none other. Such ice

holds memory in that intensity,

a siren song that calls the body.

The early dark of autumn

afternoons, the sky’s cobalt

evoke delight even as sun

departs, leading us

to the depths of night.

One fall, I sat in blue light

cast by stained glass,

a luminous veil. Amazed

by a message I heard

in prayer, I lingered

in tinted brilliance, gazed

about to see if others knew.

Was Gabriel an azure shimmer

when Mary heard him speak

the miracle to grace her life?

Often our answered prayers

are wisps of such light.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, October 7, 2024

Emperor Kangxi

Emperor Kangxi (1654—1722) — whose personal name is Xuanye — ruled in China for 61 years, during the Qing Dynasty, including for several years as a child under four regents until he came of age. He is revered for establishing a period of peace, and for encouraging the pursuits of literature and religion.

Under his influence vast encylopedias were compiled, as well as the Kangxi Chinese dictionary. In 1705, he commissioned The Complete Tang Poems —a collection of 49,000 lyric poems by more than 2,200 poets.

In 1692, Kangxi issued the Edict of Toleration, which barred attacks on churches, and legalized the practice of Christianity among Chinese people. He wanted to maintain oversite of Chinese Christians himself, and resisted the control of Pope Clement XI who issued a papal bull in 1715 condemning certain traditional Chinese religious practices. The emperor responded by banning missionaries from entering China.

Various people have sought to claim Kangxi as an adherent of their beliefs. He was a Neo-Confucian, who sponsored the construction, preservation, and restoration of many Buddhist sites, and who wrote poetry — such as the following poem of Christian faith.

The following qi-yen-she poem follows a traditional format — using seven Chinese characters in each line, and including the numbers one through ten.

基督死

功成十字血成溪 ,千丈恩流分自西。

身列四衙半夜路,徒方三背兩番鸡。

五百鞭达寸肌裂,六尺悬垂二盜齐。

慘恸八垓惊九品,七言一毕万灵啼。

The Death of Christ

When the work of the cross is done, blood flowed like a river,

Grace from the west flowed a thousand yards deep,

On the midnight road he was subjected to four trials,

Before the rooster crowed twice, three times betrayed by a disciple.

Five hundred lashes tore every inch of skin,

Two thieves hung on either side, six feet high,

Sadness greater than any had ever known,

Seven words, one completed task, ten thousand spirits weep.

Since all ten numbers don’t come through in this English translation, they are laid out here:

----1- — once for all, the finished work, or the one task

----2- — two thieves

----3- — three times denied

----4- — four trials back and forth

----5- — five hundred stripes

----6- — six feet high on the cross

----7- — the seven last words of Christ from the cross

----8- — eight compass points — to the furthermost point of the world

----9- — nine ranks of officials — all walks of people

----10 — Chinese numeral ten, which is the pictograph of the cross

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Under his influence vast encylopedias were compiled, as well as the Kangxi Chinese dictionary. In 1705, he commissioned The Complete Tang Poems —a collection of 49,000 lyric poems by more than 2,200 poets.

In 1692, Kangxi issued the Edict of Toleration, which barred attacks on churches, and legalized the practice of Christianity among Chinese people. He wanted to maintain oversite of Chinese Christians himself, and resisted the control of Pope Clement XI who issued a papal bull in 1715 condemning certain traditional Chinese religious practices. The emperor responded by banning missionaries from entering China.

Various people have sought to claim Kangxi as an adherent of their beliefs. He was a Neo-Confucian, who sponsored the construction, preservation, and restoration of many Buddhist sites, and who wrote poetry — such as the following poem of Christian faith.

The following qi-yen-she poem follows a traditional format — using seven Chinese characters in each line, and including the numbers one through ten.

基督死

功成十字血成溪 ,千丈恩流分自西。

身列四衙半夜路,徒方三背兩番鸡。

五百鞭达寸肌裂,六尺悬垂二盜齐。

慘恸八垓惊九品,七言一毕万灵啼。

The Death of Christ

When the work of the cross is done, blood flowed like a river,

Grace from the west flowed a thousand yards deep,

On the midnight road he was subjected to four trials,

Before the rooster crowed twice, three times betrayed by a disciple.

Five hundred lashes tore every inch of skin,

Two thieves hung on either side, six feet high,

Sadness greater than any had ever known,

Seven words, one completed task, ten thousand spirits weep.

Since all ten numbers don’t come through in this English translation, they are laid out here:

----1- — once for all, the finished work, or the one task

----2- — two thieves

----3- — three times denied

----4- — four trials back and forth

----5- — five hundred stripes

----6- — six feet high on the cross

----7- — the seven last words of Christ from the cross

----8- — eight compass points — to the furthermost point of the world

----9- — nine ranks of officials — all walks of people

----10 — Chinese numeral ten, which is the pictograph of the cross

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, September 30, 2024

Bede

Bede — often referred to as the Venerable Bede (673—735) — is an Anglo-Saxon poet, priest, theologian, scholar and historian. His best-known work is Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731), which outlines a history of England, beginning with the invasion by Julius Ceasar in 55 BC, and describes the conversion to Christianity of the Anglo-Saxon people. From this work came the method of dating events from Christ’s Birth (BC and AD).

At age seven, he was sent by his family to the monastery of Monkwearmouth to receive his education. He spent most of his life in the monastery, and its sister monastery at Jarrow, although he also travelled to various monasteries throughout Britain.

It is through Bede that we know that Cædmon (657—680) — besides his one surviving hymn — also wrote many poems about Genesis and the Gospels.

The following poem — also known as Bede’s Lament — is the most-copied Old English poem in ancient manuscripts; according to tradition it was written on his deathbed, although there is no evidence that he was the author. Here are a couple renderings of the poem in English. I include them both to assist us in our reflections.

Bede’s Death Song

Facing Death, that inescapable journey,

who can be wiser than he

who reflects, while breath yet remains,

on whether his life brought others happiness, or pains,

since his soul may yet win delight's or night's way

after his death-day.

Bede’s Death Song

Before the unavoidable journey there, no one becomes

wiser in thought than him who, by need,

ponders, before his going hence,

what good and evil within his soul,

after his day of death, will be judged.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

At age seven, he was sent by his family to the monastery of Monkwearmouth to receive his education. He spent most of his life in the monastery, and its sister monastery at Jarrow, although he also travelled to various monasteries throughout Britain.

It is through Bede that we know that Cædmon (657—680) — besides his one surviving hymn — also wrote many poems about Genesis and the Gospels.

The following poem — also known as Bede’s Lament — is the most-copied Old English poem in ancient manuscripts; according to tradition it was written on his deathbed, although there is no evidence that he was the author. Here are a couple renderings of the poem in English. I include them both to assist us in our reflections.

Bede’s Death Song

Facing Death, that inescapable journey,

who can be wiser than he

who reflects, while breath yet remains,

on whether his life brought others happiness, or pains,

since his soul may yet win delight's or night's way

after his death-day.

Bede’s Death Song

Before the unavoidable journey there, no one becomes

wiser in thought than him who, by need,

ponders, before his going hence,

what good and evil within his soul,

after his day of death, will be judged.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, September 23, 2024

Luke Harvey

Luke Harvey is a poet who describes himself as “living in the interstate / between two worlds” — that is, in Chickamauga, Georgia, just ten miles from Chattanooga, Tennessee. He works as a high school teacher in that other world. He also writes for and works on the poetry editorial panel for The Rabbit Room.

Harvey’s debut poetry collection Let’s Call It Home has just appeared as part of the Poiema Poetry Series from Cascade Books. I am honoured to have worked with Luke in editing this fine book for publication.

The English poet Malcolm Guite has written of this new collection, “Time and again these poems do what poetry does best: they transfigure the familiar and so reveal something of its meaning: …from the mystery of the earthworm rising towards the rain, to the family who find that feeding a child pureed peas is an entirely sacramental act, in poem after poem Luke Harvey gives us a glimpse of what George Herbert called ‘Heaven in Ordinary’.”

The following poem is from Let’s Call It Home.

After the Murder

The crux of the matter is what to do.

with the body now crumbled

in your hands. Logic says dismember

it, scrubbing beneath your fingernails

to rinse away any condemning

evidence of having been at the scene

of the slaughter, then bury the axe.

Or maybe you play it cool, act

like it’s nothing new to hold a carcass

in your cupped palms, like really this

is something you do on a weekly basis,

nonchalant as a Sunday stroll. Of course,

you wouldn’t be here in the first place

if you were one to listen to logic,

so disregard that. You’re holding the flesh

and blood of another. This is no time for logic.

Pray for forgiveness and devour it,

wiping first one cheek, then the other.

Posted with permission of the poet.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Harvey’s debut poetry collection Let’s Call It Home has just appeared as part of the Poiema Poetry Series from Cascade Books. I am honoured to have worked with Luke in editing this fine book for publication.

The English poet Malcolm Guite has written of this new collection, “Time and again these poems do what poetry does best: they transfigure the familiar and so reveal something of its meaning: …from the mystery of the earthworm rising towards the rain, to the family who find that feeding a child pureed peas is an entirely sacramental act, in poem after poem Luke Harvey gives us a glimpse of what George Herbert called ‘Heaven in Ordinary’.”

The following poem is from Let’s Call It Home.

After the Murder

The crux of the matter is what to do.

with the body now crumbled

in your hands. Logic says dismember

it, scrubbing beneath your fingernails

to rinse away any condemning

evidence of having been at the scene

of the slaughter, then bury the axe.

Or maybe you play it cool, act

like it’s nothing new to hold a carcass

in your cupped palms, like really this

is something you do on a weekly basis,

nonchalant as a Sunday stroll. Of course,

you wouldn’t be here in the first place

if you were one to listen to logic,

so disregard that. You’re holding the flesh

and blood of another. This is no time for logic.

Pray for forgiveness and devour it,

wiping first one cheek, then the other.

Posted with permission of the poet.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, September 16, 2024

Adam Mickiewicz*

Adam Mickiewicz (1798—1855) is often referred to as Poland’s greatest poet. “He was at once the Homer and the Dante of the Polish nation,” said the poet and critic Jan Lechoń.

In 1824, after having been briefly imprisoned for pro-Polish independence activities, Mickiewicz was banished to Russia. He quickly became popular in the literary society of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, and befriended Alexander Pushkin. After five years of exile he was given permission to travel to Europe; he settled in Rome, and later in Paris.

In the Preface to the book Metaphysical Poems (2023, Brill) — which includes essays about Mickiewicz and a large selection of his poems (both in the original Polish and in English translation) — the selection of poems are said to show Mickiewicz to be,

----“…part of the diverse culture of European Romanticism, as well

----as the great metaphysical and mystical tradition extending from

----the classical culture of Greece and Rome, through mediaeval

----Christendom, to the early-modern Reformation and Enlightenment.

----In these poems Mickiewicz testifies to a spiritual longing for God

----and the meaning of human existence, a longing which transcends not

----only national, ethnic and linguistic boundaries, but also

----religious denominations.”

The following poem was translated by Mateusz Stróżyński and Jaspreet Singh Boparai and appears in Metaphysical Poems (2023 Brill).

Reason and Faith

When I have bowed proud reason and my head

Before the Lord like clouds before the sun:

The Lord raised them up like a rainbow bright

And painted them with myriad dazzling rays.

And it will shine, a witness to our faith,

When from the heavenly dome disaster flows;

And when we fear the flood, the rainbow will

Remind us of the covenant once more.

Oh, Lord! Humility has made me proud,

For even though I shine in heavenly realm —

My Lord! — the shine’s not mine! It’s but a weak

Reflection of your glorious, dazzling fires!

I looked upon the lowly realms of Man,

On his opinions’ varying tones and hues:

To reason they appeared large and confused,

But to the eyes of faith they’re small, and clear

All the proud scholars! Also you I see!

The storm is throwing you around like trash.

You are enclosed like snails in little shells,

While you desire to comprehend the globe.

They claim: “Necessity! It blindly rules

The world like the moon which governs the waves.”

While others say: “It’s Accident which plays

In Man like winds that frolic in the sky.”

There is a Lord who has embraced the sea

And made it trouble Earth eternally;

But carved for it the boundary in rock,

Designed to act as an eternal check.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Adam Mickiewicz: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

In 1824, after having been briefly imprisoned for pro-Polish independence activities, Mickiewicz was banished to Russia. He quickly became popular in the literary society of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, and befriended Alexander Pushkin. After five years of exile he was given permission to travel to Europe; he settled in Rome, and later in Paris.

In the Preface to the book Metaphysical Poems (2023, Brill) — which includes essays about Mickiewicz and a large selection of his poems (both in the original Polish and in English translation) — the selection of poems are said to show Mickiewicz to be,

----“…part of the diverse culture of European Romanticism, as well

----as the great metaphysical and mystical tradition extending from

----the classical culture of Greece and Rome, through mediaeval

----Christendom, to the early-modern Reformation and Enlightenment.

----In these poems Mickiewicz testifies to a spiritual longing for God

----and the meaning of human existence, a longing which transcends not

----only national, ethnic and linguistic boundaries, but also

----religious denominations.”

The following poem was translated by Mateusz Stróżyński and Jaspreet Singh Boparai and appears in Metaphysical Poems (2023 Brill).

Reason and Faith

When I have bowed proud reason and my head

Before the Lord like clouds before the sun:

The Lord raised them up like a rainbow bright

And painted them with myriad dazzling rays.

And it will shine, a witness to our faith,

When from the heavenly dome disaster flows;

And when we fear the flood, the rainbow will

Remind us of the covenant once more.

Oh, Lord! Humility has made me proud,

For even though I shine in heavenly realm —

My Lord! — the shine’s not mine! It’s but a weak

Reflection of your glorious, dazzling fires!

I looked upon the lowly realms of Man,

On his opinions’ varying tones and hues:

To reason they appeared large and confused,

But to the eyes of faith they’re small, and clear

All the proud scholars! Also you I see!

The storm is throwing you around like trash.

You are enclosed like snails in little shells,

While you desire to comprehend the globe.

They claim: “Necessity! It blindly rules

The world like the moon which governs the waves.”

While others say: “It’s Accident which plays

In Man like winds that frolic in the sky.”

There is a Lord who has embraced the sea

And made it trouble Earth eternally;

But carved for it the boundary in rock,

Designed to act as an eternal check.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about Adam Mickiewicz: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, September 9, 2024

Seamus Heaney*

Seamus Heaney (1939—2013) is one of Ireland’s most respected poets. He grew up in the north and — not for political or religious reasons — moved to the south in 1972. He has also been shared by the US (he taught for one semester a year at Harvard for 20 years) and England (he was Poetry Professor at Oxford for five years).

In his poetry he frequently preserves memories of the past — the sound and feel of how tasks were accomplished during his childhood, other aspects of the way rural life was, and memories of family, church, and school life. He said, “Almost always [a poem] starts from some memory, something you’d forgotten that comes up like a living gift of presence.” For Heaney, though, such thoughts require further reflection. “That is the kind of poem I really like: the stimulus in memory, but the import, hopefully, more than just the content of memory.”

The following poem is, by my count, the third time Heaney has taken on this story from the Gospels (Matthew 9, Mark 2, Luke 5). The first was in his book Seeing Things (1991), the second in Human Chain (2010) — and this one appeared in Poetry Ireland Review in 2014, after Heaney’s death. As far as I know, it has not been collected in a posthumous poetry collection.

The Latecomers

He saw them come, then halt behind the crowd

That wailed and plucked and ringed him, and was glad

They kept their distance. Hedged on every side,

Harried and responsive to their need,

Each hand that stretched, each brief hysteric squeal –

However he assisted and paid heed,

A sudden blank letdown was what he’d feel

Unmanning him when he met the pain of loss

In the eyes of those his reach had failed to bless.

And so he was relieved the newcomers

Had now discovered they’d arrived too late

And gone away. Until he hears them, climbers

On the roof, a sound of tiles being shifted,

The treble scrape of terra cotta lifted

And a paralytic on his pallet

Lowered like a corpse into a grave,

Exhaustion and the imperatives of love

Vied in him. To judge, instruct, reprove,

And ease them body and soul.

Not to abandon but to lay on hands.

Make time. Make whole. Forgive.

*This is the fourth Kingdom Poets post about Seamus Heaney: first post, second post, third post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

In his poetry he frequently preserves memories of the past — the sound and feel of how tasks were accomplished during his childhood, other aspects of the way rural life was, and memories of family, church, and school life. He said, “Almost always [a poem] starts from some memory, something you’d forgotten that comes up like a living gift of presence.” For Heaney, though, such thoughts require further reflection. “That is the kind of poem I really like: the stimulus in memory, but the import, hopefully, more than just the content of memory.”

The following poem is, by my count, the third time Heaney has taken on this story from the Gospels (Matthew 9, Mark 2, Luke 5). The first was in his book Seeing Things (1991), the second in Human Chain (2010) — and this one appeared in Poetry Ireland Review in 2014, after Heaney’s death. As far as I know, it has not been collected in a posthumous poetry collection.

The Latecomers

He saw them come, then halt behind the crowd

That wailed and plucked and ringed him, and was glad

They kept their distance. Hedged on every side,

Harried and responsive to their need,

Each hand that stretched, each brief hysteric squeal –

However he assisted and paid heed,

A sudden blank letdown was what he’d feel

Unmanning him when he met the pain of loss

In the eyes of those his reach had failed to bless.

And so he was relieved the newcomers

Had now discovered they’d arrived too late

And gone away. Until he hears them, climbers

On the roof, a sound of tiles being shifted,

The treble scrape of terra cotta lifted

And a paralytic on his pallet

Lowered like a corpse into a grave,

Exhaustion and the imperatives of love

Vied in him. To judge, instruct, reprove,

And ease them body and soul.

Not to abandon but to lay on hands.

Make time. Make whole. Forgive.

*This is the fourth Kingdom Poets post about Seamus Heaney: first post, second post, third post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Labels:

Seamus Heaney

Monday, September 2, 2024

Ann Griffiths*

Ann Griffiths (1776—1805) is a hymnist of rural Wales whose poetic achievement is treasured by those who speak the Welsh language. She grew up in a family who faithfully attended their parish church and, like their neighbours, enjoyed traditional noson lawen evenings of singing with the harp and dancing.

In the mid-1790s, she embraced the spiritual renewal of the Methodist revival that was sweeping through Wales. This is when she began composing her hymns and poems, only a few of which she actually wrote down.

She recited them to her friend Ruth Hughes, who also committed them to memory. After Ann Griffiths died, it was Ruth’s husband, John Hughes, who published them. John was a teacher and preacher who had corresponded extensively with Ann as a spiritual mentor.

In the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, Gomer Morgan Roberts describes her verse as “characterized by a wealth of scriptural allusion, by deep religious and mystical feeling, and by bold metaphors.”