Monday, August 26, 2024

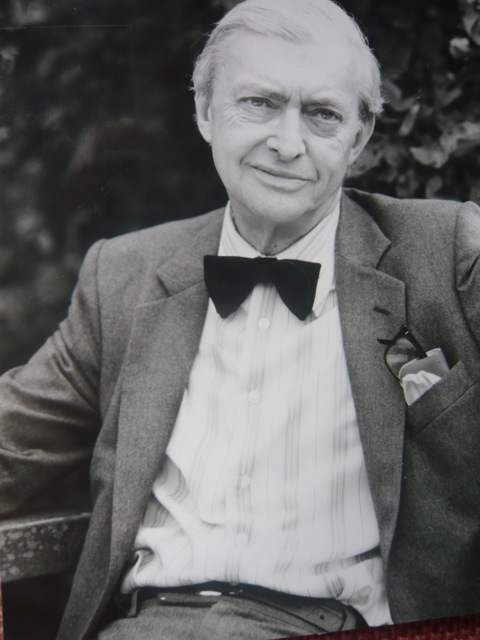

Andrew Lansdown*

Andrew Lansdown is a significant Australian poet. His new collection, The Farewell Suites has just been published by Cascade Books as part of the Poiema Poetry Series.

Fransesca Stewart wrote of his Abundance: New & Selected Poems (2020, Poiema/Cascade) in Westerly Magazine from the University of Western Australia,

-----“Abundance offers a rich and varied view of the world through

-----Lansdown’s eyes. By noticing the miraculous and the mundane,

-----and with an ever-present awareness of the passing of time,

-----these poems pay attention to ordinary life and bring a captivating

-----intensity of presence and emotion. Lansdown… by turning the poetic

-----gaze upon himself… displays acute self-awareness and disarming

-----vulnerability in observing his mind, emotions and reactions to life.”

With his new poetry collection, Andrew Lansdown becomes even more publicly vulnerable. Here he carries us through all the heartache of losing loved ones — the death of three brothers, his wife’s miscarriage, and the final farewell to a dearly loved mother and father. For the rest of us, who have experienced varying degrees of the same thing — or who soon will — The Farewell Suites is an eloquent reminder that in this we are not alone.

I am honoured to have worked with Andrew as his editor for both of these books.

Lamplight

The lamp of the Lord—

that’s how the word of the Lord

describes the spirit of a man.

And looking at my father

sunken into his deathbed

I sense and see the truth of it.

Now his spirit has returned

(a little ruined, a lot redeemed)

to the Lord who gave it,

how dark it is, his body,

how utterly given over

to bleakness and blackness,

its lamplight all extinguished.

Posted with permission of the poet.

*This is the third Kingdom Poets post about Andrew Lansdown: first post, second post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, August 19, 2024

Venantius Fortunatus

Venantius Fortunatus (c. 530—c. 609) is a Latin poet who was born in the northeast of what is now Italy, and was educated at Ravenna. He later travelled as a wandering minstrel, and as a pilgrim to worship at the shrine of St Martin in Tours and other shrines. It is believed that his intent in moving to Metz, in what is now Northeast France, was to become a poet at the Merovingian Court.

Fortunatus performed a celebration poem for a royal wedding in 566, and soon found patrons among the nobility and bishops. Around 576 he was ordained, and by around 600 he became the Bishop of Poitiers.

The following poem was translated in the 19th century from the Latin by Edward Caswall. It appears in Burl Horniachek’s anthology, To Heaven’s Rim: The Kingdom Poets Book of World Christian Poetry.

Sing, My Tongue, the Saviour’s Glory

Sing, my tongue, the Saviour's glory;

Tell His triumph far and wide;

Tell aloud the famous story

Of His body crucified;

How upon the cross a victim,

Vanquishing in death, He died.

Eating of the tree forbidden,

Man had sunk in Satan’s snare,

When our pitying Creator did

This second tree prepare;

Destined, many ages later,

That first evil to repair.

Such the order God appointed

When for sin He would atone;

To the serpent thus opposing

Schemes yet deeper than his own;

Thence the remedy procuring,

Whence the fatal wound had come.

So when now at length the fullness

of the sacred time drew nigh,

Then the Son, the world’s Creator,

Left his Father’s throne on high;

From a virgin’s womb appearing,

Clothed in our mortality.

All within a lowly manger,

Lo, a tender babe He lies!

See his gentle Virgin Mother

Lull to sleep his infant cries!

While the limbs of God incarnate

‘Round with swathing bands she ties.

Thus did Christ to perfect manhood

In our mortal flesh attain:

Then of His free choice He goeth

To a death of bitter pain;

And as a lamb, upon the altar of the cross,

For us is slain.

Lo, with gall His thirst He quenches!

See the thorns upon His brow!

Nails His tender flesh are rending!

See His side is opened now!

Whence, to cleanse the whole creation,

Streams of blood and water flow.

Faithful Cross! Above all other,

One and only noble Tree!

None in foliage, none in blossom,

None in fruit thy peers may be;

Sweetest wood and sweetest iron!

Sweetest Weight is hung on thee!

Lofty tree, bend down thy branches,

To embrace thy sacred load;

Oh, relax the native tension

Of that all too rigid wood;

Gently, gently bear the members

Of thy dying King and God.

Tree, which solely wast found worthy

The world’s Victim to sustain.

Harbor from the raging tempest!

Ark, that saved the world again!

Tree, with sacred blood anointed

Of the Lamb for sinners slain.

Blessing, honour, everlasting,

To the immortal Deity;

To the Father, Son, and Spirit,

Equal praises ever be;

Glory through the earth and heaven

To Trinity in Unity. Amen

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Fortunatus performed a celebration poem for a royal wedding in 566, and soon found patrons among the nobility and bishops. Around 576 he was ordained, and by around 600 he became the Bishop of Poitiers.

The following poem was translated in the 19th century from the Latin by Edward Caswall. It appears in Burl Horniachek’s anthology, To Heaven’s Rim: The Kingdom Poets Book of World Christian Poetry.

Sing, My Tongue, the Saviour’s Glory

Sing, my tongue, the Saviour's glory;

Tell His triumph far and wide;

Tell aloud the famous story

Of His body crucified;

How upon the cross a victim,

Vanquishing in death, He died.

Eating of the tree forbidden,

Man had sunk in Satan’s snare,

When our pitying Creator did

This second tree prepare;

Destined, many ages later,

That first evil to repair.

Such the order God appointed

When for sin He would atone;

To the serpent thus opposing

Schemes yet deeper than his own;

Thence the remedy procuring,

Whence the fatal wound had come.

So when now at length the fullness

of the sacred time drew nigh,

Then the Son, the world’s Creator,

Left his Father’s throne on high;

From a virgin’s womb appearing,

Clothed in our mortality.

All within a lowly manger,

Lo, a tender babe He lies!

See his gentle Virgin Mother

Lull to sleep his infant cries!

While the limbs of God incarnate

‘Round with swathing bands she ties.

Thus did Christ to perfect manhood

In our mortal flesh attain:

Then of His free choice He goeth

To a death of bitter pain;

And as a lamb, upon the altar of the cross,

For us is slain.

Lo, with gall His thirst He quenches!

See the thorns upon His brow!

Nails His tender flesh are rending!

See His side is opened now!

Whence, to cleanse the whole creation,

Streams of blood and water flow.

Faithful Cross! Above all other,

One and only noble Tree!

None in foliage, none in blossom,

None in fruit thy peers may be;

Sweetest wood and sweetest iron!

Sweetest Weight is hung on thee!

Lofty tree, bend down thy branches,

To embrace thy sacred load;

Oh, relax the native tension

Of that all too rigid wood;

Gently, gently bear the members

Of thy dying King and God.

Tree, which solely wast found worthy

The world’s Victim to sustain.

Harbor from the raging tempest!

Ark, that saved the world again!

Tree, with sacred blood anointed

Of the Lamb for sinners slain.

Blessing, honour, everlasting,

To the immortal Deity;

To the Father, Son, and Spirit,

Equal praises ever be;

Glory through the earth and heaven

To Trinity in Unity. Amen

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, August 12, 2024

David Gascoyne*

David Gascoyne (1916—2001) is an English poet whose first poetry collection appeared when he was just sixteen. He travelled to Paris in 1933 and became not only influenced by the surrealist movement, but became its spokesman to Britain — translating the poetry of Salvador Dali, Benjamin Peret, and André Breton.

Gascoyne also became a significant poet himself, writing original surrealist verse in his well-received second book of poems Man’s Life Is This Meat. By his third collection, however he had lost faith in surrealism, and began writing the mystical poems of an anguished Christian seeker. Elizabeth Jennings wrote, “I do not think … he really found his own voice or his own individual means of expression until he started writing the poems which appeared in the volume entitled Poems, 1937–42…”

The following poem is one of them, which was written in 1938.

Kyrie

Is man’s destructive lust insatiable? There is

Grief in the blow that shatters the innocent face.

Pain blots out clearer sense. And pleasure suffers

The trial thrust of death in even the bride’s embrace.

The black catastrophe that can lay waste our worlds

May be unconsciously desired. Fear masks our face;

And tears as warm and cruelly wrung as blood

Are tumbling even in the mouth of our grimace.

How can our hope ring true? Fatality of guilt

And complicated anguish confounds time and place;

While from the tottering ancestral house an angry voice

Resounds in prophecy. Grant us extraordinary grace,

O spirit hidden in the dark in us and deep,

And bring to light the dream out of our sleep.

The following is one version of a piece by Gascoyne from his New Collected Poems, although I’ve encountered a significantly different version elsewhere.

The Son of Man is in Revolt

The Son of Man is in revolt

Against the god of men.

The Son of God who took the fault

Of men away from them

To lay it in himself on God

Has nowhere now to rest God’s head

But in the heart of human solitude.

*This is the second Kingdom Poets post about David Gascoyne: first post.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Monday, August 5, 2024

Jack Ridl

Jack Ridl is an American poet who served for 37 years as a professor at Hope College in Holland, Michigan. Two of his recent poetry collections are Saint Peter and the Goldfinch (2019) and Practicing to Walk Like a Heron (2013) which won the National Gold Medal for poetry by ForeWord Reviews; both were published by Wayne State University Press.

His newest collection, All at Once, will be published by CavanKerry Press this fall. Check out his “Letter to an Aspiring Poet” published earlier this year at Reformed Journal.

In 1996 The Carnegie (CASE) Foundation named him Michigan Professor of the Year. Perhaps a greater tribute to his teaching, is that nine of his students are included in Naomi Shihab Nye’s anthology Time You Let Me In: 25 Poets Under 25 (2010, HarperCollins), more than 90 of Jack’s students have earned MFA degrees, and more than 100 are published authors.

The following poem first appeared in Image.

Bartholemew: Disciple

I never knew what was going on.

He would say, “Let’s go,” and we

would follow. “Follow” was his word.

And we would. Fools we were to let that

take us all that way. Why we did to this day

I don’t know. Look how it ended. Look

what it became. But what did we have

to stay for? Nothing. There wasn’t much

work. Nothing much to do. There were no

stories left. Bread. Fish. So we ended up

with more bread and fish. But we did find

stories and stories. Well, what else is there?

I never did much along the way. Look it up.

In the big deal painting I’m the one who appears

rather glassy eyed, and believe me, it wasn’t the wine.

I just went along. The miracles had been done before.

I will say, though, that it was his words. Words!

Imagine. Words had never done what his did.

I’d listen, and I wasn’t much of a listener. Then

later I would try to make sense of them. I couldn’t.

But I could feel them. And maybe that was it, how

they got inside you and made you wonder and wrinkle.

They got in my brain’s garden and made it seem like

the roots were above ground and all the flowers and

vegetables, all the nourishing, were now below.

He didn’t reverse things, exactly—the first shall be

last and the last first and all that. It was that everything

changed inside me when he said those things. It was

what happened to me. I started looking at lepers and the poor

and paid no attention anymore to the kings and scribes and

Pharisees. I had thought the world of them. Now they seemed

unimportant in their importance. See? See how hard it is to

explain this stuff? You just started seeing everything with a

new mind. You began to be drawn to a whole new world,

and it was a world. Like now. A world within a world, one

drawing you, the other imposing itself on you. Why am I

telling you what you already know? Erosions. That’s it.

The reversals were erosions. And in what was left, I

wanted to plant what didn’t belong. Lilies in fields.

You might say, okay, whatever, and yet those words

did become flesh, my flesh. And my flesh, my body, held

the kingdom of God, and if it’s a place that’s a place

for children, then most of what I know really doesn’t matter.

Labor doesn’t, and money, and reason, and, well, you

go make a list. He’d get me so confused. And then we’d

head off worrying about how we would eat and where

we’d sleep. Our feet were filthy. My God, we were always

filthy. We stank. And then he’d go and point at birds or

stalks of grain, even stop and have us kneel before a flower,

and then he’d smile. That haunts me still. That smile.

And then he died. He brought out hate, not love. He had

a terrifying sense of justice. Nothing he said or did

was impossible. Maybe that was it. It was all possible.

Posted with permission of the poet.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

His newest collection, All at Once, will be published by CavanKerry Press this fall. Check out his “Letter to an Aspiring Poet” published earlier this year at Reformed Journal.

In 1996 The Carnegie (CASE) Foundation named him Michigan Professor of the Year. Perhaps a greater tribute to his teaching, is that nine of his students are included in Naomi Shihab Nye’s anthology Time You Let Me In: 25 Poets Under 25 (2010, HarperCollins), more than 90 of Jack’s students have earned MFA degrees, and more than 100 are published authors.

The following poem first appeared in Image.

Bartholemew: Disciple

I never knew what was going on.

He would say, “Let’s go,” and we

would follow. “Follow” was his word.

And we would. Fools we were to let that

take us all that way. Why we did to this day

I don’t know. Look how it ended. Look

what it became. But what did we have

to stay for? Nothing. There wasn’t much

work. Nothing much to do. There were no

stories left. Bread. Fish. So we ended up

with more bread and fish. But we did find

stories and stories. Well, what else is there?

I never did much along the way. Look it up.

In the big deal painting I’m the one who appears

rather glassy eyed, and believe me, it wasn’t the wine.

I just went along. The miracles had been done before.

I will say, though, that it was his words. Words!

Imagine. Words had never done what his did.

I’d listen, and I wasn’t much of a listener. Then

later I would try to make sense of them. I couldn’t.

But I could feel them. And maybe that was it, how

they got inside you and made you wonder and wrinkle.

They got in my brain’s garden and made it seem like

the roots were above ground and all the flowers and

vegetables, all the nourishing, were now below.

He didn’t reverse things, exactly—the first shall be

last and the last first and all that. It was that everything

changed inside me when he said those things. It was

what happened to me. I started looking at lepers and the poor

and paid no attention anymore to the kings and scribes and

Pharisees. I had thought the world of them. Now they seemed

unimportant in their importance. See? See how hard it is to

explain this stuff? You just started seeing everything with a

new mind. You began to be drawn to a whole new world,

and it was a world. Like now. A world within a world, one

drawing you, the other imposing itself on you. Why am I

telling you what you already know? Erosions. That’s it.

The reversals were erosions. And in what was left, I

wanted to plant what didn’t belong. Lilies in fields.

You might say, okay, whatever, and yet those words

did become flesh, my flesh. And my flesh, my body, held

the kingdom of God, and if it’s a place that’s a place

for children, then most of what I know really doesn’t matter.

Labor doesn’t, and money, and reason, and, well, you

go make a list. He’d get me so confused. And then we’d

head off worrying about how we would eat and where

we’d sleep. Our feet were filthy. My God, we were always

filthy. We stank. And then he’d go and point at birds or

stalks of grain, even stop and have us kneel before a flower,

and then he’d smile. That haunts me still. That smile.

And then he died. He brought out hate, not love. He had

a terrifying sense of justice. Nothing he said or did

was impossible. Maybe that was it. It was all possible.

Posted with permission of the poet.

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the author of five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021, Cascade) ― a book of poems written from the point-of-view of angels. His books are available through Wipf & Stock.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)